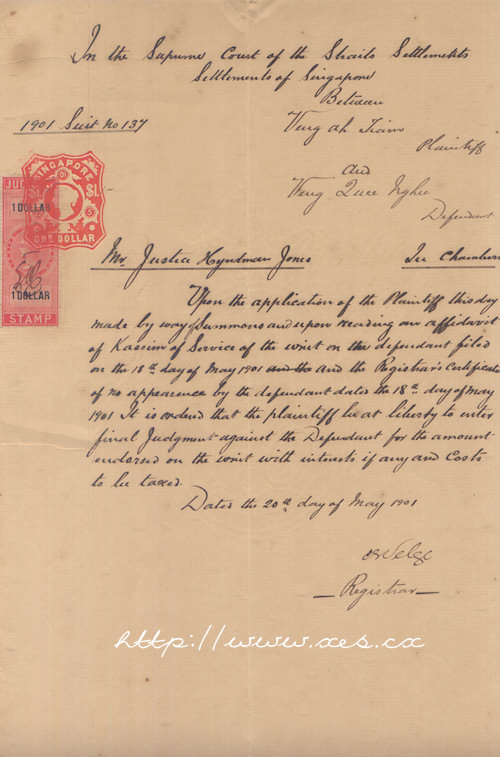

Court order dated 20.5.1901 (Front)

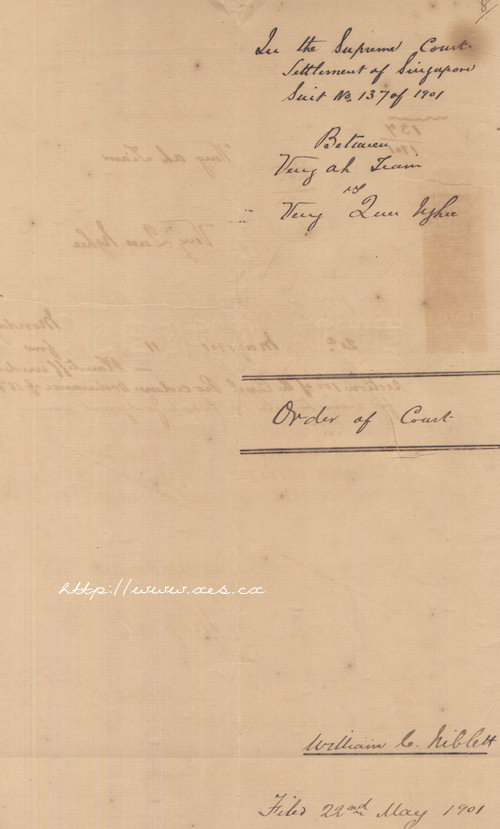

Court order dated 20.5.1901 (Back)

It’s amazing how a piece of document like this has so much history. This order was prepared by Messrs William C. Nibblet of No. 2, Raffles Place, Singapore.

Raffles Place in the 1920s

While many Straits Settlement lawyers were praised in old records, Mr. Nibblet didn’t share such fortune. In fact, his name was not even mentioned in the book “One hundred years of Singapore” written by Braddell, Roland St. John; Brooke, Gilbert Edward; Makepeace, Walter in 1921.

According to an article titled “Bride becomes Lunatic“, his insane wife divorced him accusing him to have committed adultery and bigamy. Subsequently, he was sentenced to 1 month jail for bigamy. However, his counsel said that he is almost blind.

Before this happened, he was once charged for contempt. In an article entitled “The Alleged Charge of Contempt Against A Solicitor” (1893), he was charged for contempt for refusing to accept service of a document and allegedly threatened the process server.

He died on 30th April 1920.

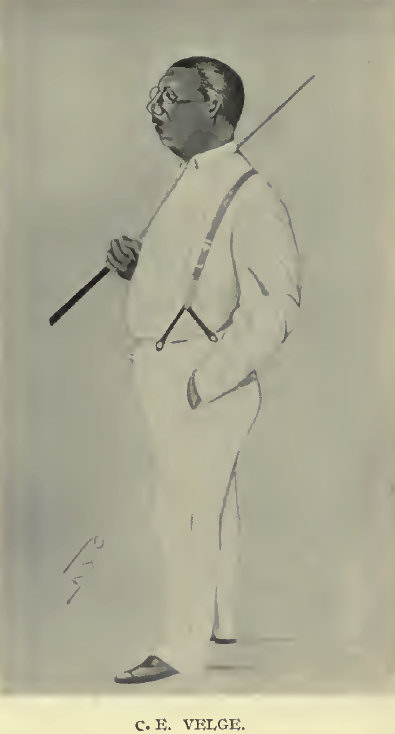

This order was signed by C. E. Velge. His signature appears on many of my old Straits Settlement documents.

There is only a short biography of him in the book.

When Mr. Christian Baumgarten resigned the appointment of Registrar in 1874, the post went to Mr. Charles Eugene Velge. He was a son of Mr. J. H. Velge, who was well-known in Singapore in the old days for his hospitality. Mr. C. E. Velge had been called to the Bar at the Middle Temple in 1 870. He held the Registrarship until 1907, at the end of which year he retired, dying in September 1912. Mr. Velge was a splendid Registrar, and throughout his long career held the complete confidence of Bench and Bar. He was exceedingly fond of racing, and was as good a judge of a racehorse’s capacities as any man who has been out here.

The Judge who gave this order was Sir William Hyndman Jones, the former Chief Justices of the Straits Settlements from 1906-1914.

In 1897 Sir William Henry Hyndman-Jones was appointed to the Straits Bench. He was born in 1847, the son of Mr. William Henry Jones, of Upper Norwood, and was educated at Marlborough and Trinity College, Cambridge. In 1878 he was called to the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn, and was sent in 1880 to enquire into the working and administration of the Barbados Police Force. The next year he was appointed to act as a Judge of the Barbados Court of Appeal. After serving in various legal capacities in the West Indies, he was appointed to the Straits Bench.

In January 1906 he became Chief Judicial Commissioner of the Federated Malay States, and in August of that year Chief Justice of the Straits Settlements. He retired in 1914. His successor, Sir John Bucknill, in a speech which he made to the Bar on taking his seat, referred to Sir William as the ” Nestor of the Colonial Bench,” and a more apt description could not have been given. The Bar hoped that he would be appointed to the Privy Council, a distinction which he more than deserved, but the appointment was not made, and Sir William lives in retirement at Jersey.

Sir William was the beau ideal of a Judge, learned, quick at grasping law and fact ; of most stately presence, and possessed of a fine figure, he dominated his Court, and filled it with an atmosphere of dignity that accorded with the finest traditions of the Bench. Courteous and kind, he had always a helping hand for the struggling junior, and he certainly taught more law and more etiquette to the younger members of the Bar than any Judge who has ever sat here. Jurymen speak of him in the highest admiration, but to the Bar he was perhaps at his best when presiding over the Court of Appeal. Counsel were kept to the point, decisions were rapid ; there was no constant interruption, no wrangling with Counsel, and work in the Court of Appeal, while he presided, was a pleasure and often an education.

He was possessed of a strong sense of humour, but it did not evince itself by jokes. He had a habit of placing his handkerchief over his mouth when anything appealed to his risibility ; but the blue eyes over the handkerchief told their tale, and the Counsel who could call a twinkle into them by a witty remark did not find his task any the more difficult in consequence. When he said anything humorous he did it in such a dry and logical way that it became all the more funny. During the hearing of the Appeal in the Six Widows Case he convulsed the whole Court by a little passage which he had with the late Mr. Montagu Harris.

Mr. Harris was a very sparkling and amusing speaker, but he was not very logical, and in the course of his argument he invited the Court of Appeal to step into the shoes of the deceased Choo Eng Choon, to which Sir William drily replied that in that event the Court would be assembled elsewhere. Harris retorted that he meant during Choo Eng Choon ‘s lifetime, to which Sir William further replied that in that case the Court would have nothing to do with the matter ! Sir William was the only Judge who could deal effectually with Mr. Harris, and he did it always in so kindly, humorous a way that the latter had to accept defeat.

When the same case was before Sir Archibald Law, Mr. Harris waxed very indignant at the attempt to upset his client’s rights. ” It is unreasonable,” he said, ” for my learned friends to come here with antiquated Chinese laws and attempt to upset the law of this Colony

in half-an-hour !

“Sir Archibald said with a groan : ” Half an hour ” !

“In four days, you mean !”

“What is four days in eternity, my Lord ? ” Getting no reply, Mr. Harris answered himself by saying, ‘ ‘ A mere drop in the ocean!” And to those engaged in the case it certainly seemed to be eternity before we had done with it.

I bet if I tell a Judge, “What is four days in eternity, my Lord “, I will get kicked out from the Court.

He died at the age of 79 on 20 August 1962 in England.

While reading the “‘One hundred years of Singapore History”, I found that in the past people actually place bets on Court decisions. In the following passage, the author tells us that there was a case where a crowd applauded when a man charged for murder was acquitted.

In 1912 another little Malay boy was cruelly murdered, the body being thrown into the sea opposite Raffles’s Reclamation, where it was observed by a police officer at low tide. A Malay named Effendi was arrested and tried for the murder before Sir William Hyndman-Jones, the Chief Justice, and a special jury. After a trial lasting six days the accused was acquitted, and the authorship of the murder remains a mystery. On the last day, when the verdict was given, the Chief Justice’s Court was crowded almost to suffocation, natives filling every available space, standing in the corridors, and even down the stairs, and right out into the space between the Court and the Victoria Memorial Hall, so that far more than three-quarters of them could see and hear nothing, but had merely come to await the verdict. When the Jury returned to Court, after a short retirement, and acquitted the accused, there was a loud and prolonged outburst of applause, the reason for which was by no means gratification at the triumph of innocence. The case for the Crown was circumstantial, and was most powerfully, though absolutely fairly, presented by Mr. George Seth, Deputy Public Prosecutor at the time.

Singapore at that time suffered from an epidemic of book-makers, which had in the end to be stamped out by the passing of an Ordinance making betting an offence. One of the fraternity was in Court and heard Mr. Seth’s opening, with the result that he commenced betting long odds upon a conviction. These odds dropped day by day as the defence played their cards ;but he had made a very bad book, and though he hedged towards the end of the trial, it appeared that the loud applause was due to successful bets. These facts, which came out after the trial, had a good deal to do with the eventual driving of the book-makers out of the place, as the Chief Justice on hearing of them was naturally much incensed.